This is Backlog Roulette, a series in which I randomly pick an unplayed game from my backlog and play it. As always, you may click on images to view larger versions.

Reader, brace yourself for a chilling glimpse into my psyche. Like many people, I have a huge backlog of games, acquired from various digital sales, bundles, and the like. Unlike most people, I’ve organized mine in a giant spreadsheet, tracking where I got the games from (Steam, GOG, Humble, etc.) and including other useful notes, like whether I’ve played the game already, or whether a game comes with a bundled soundtrack or other extras. This helps me organize all my games — well, not all of them, the gigantic itch.io bundle is a whole other can of worms — but even so, I often forget what some games are. A little while back, inspired by my Scratching That Itch series, I decided to pick one of the unplayed games from my backlog at random and try it out.

The virtual dice picked a game called Wild Metal Country. Not only did I have no memory of what this game is or when I acquired it, I saw that I’d listed the source as a “Digital Installer”. This means I didn’t get it from any of the major digital storefronts, but rather had downloaded an installer from an unknown location at some point and stored it on a backup drive. The mystery deepened. It was time to discover just what the hell Wild Metal Country is.

What Wild Metal Country is, reader, is a 1999 game from DMA Design, the studio that would become Rockstar Games (or more accurately Rockstar North), who are now much more famous as the makers of the behemoth Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead franchises. In fact, they’d already made the first Grand Theft Auto game in 1997, and the second would release shortly after Wild Metal Country. But in the ’90s they were perhaps better known for the Lemmings series, which had seen multiple entries by the time Wild Metal Country appeared, and they were still developing a selection of other titles as well.

Wild Metal Country — which was re-released in digital form for free in 2004, which is presumably when I grabbed it — is perhaps the last game that DMA Design made before the Grand Theft Auto games became their sole focus, and it’s refreshingly odd. It’s a game about sci-fi tanks, but it has the kind of playful, experimental design that I recall from other PC games in the ’90s, games that are not often remembered today but were weird or interesting enough to be compelling, at least for a while. In Wild Metal Country’s case, the developers were clearly excited by physics systems, and built something to take advantage of them. At the time, realistic physics in games didn’t really exist. We didn’t have ragdolls in games, or objects that could be knocked over or tossed around in a realistic manner. That all started in the late ’90s, and arguably didn’t become an essential feature until Half-Life 2 in 2004. There’s a decent chance that someone playing Wild Metal Country on release would have never seen believable phsyics in a 3D game before. The only such game I know of that predates Wild Metal Country is Trespasser, which released in 1998, and I recall reviews discussing how its physics were impressive but couldn’t really hold the whole game together.

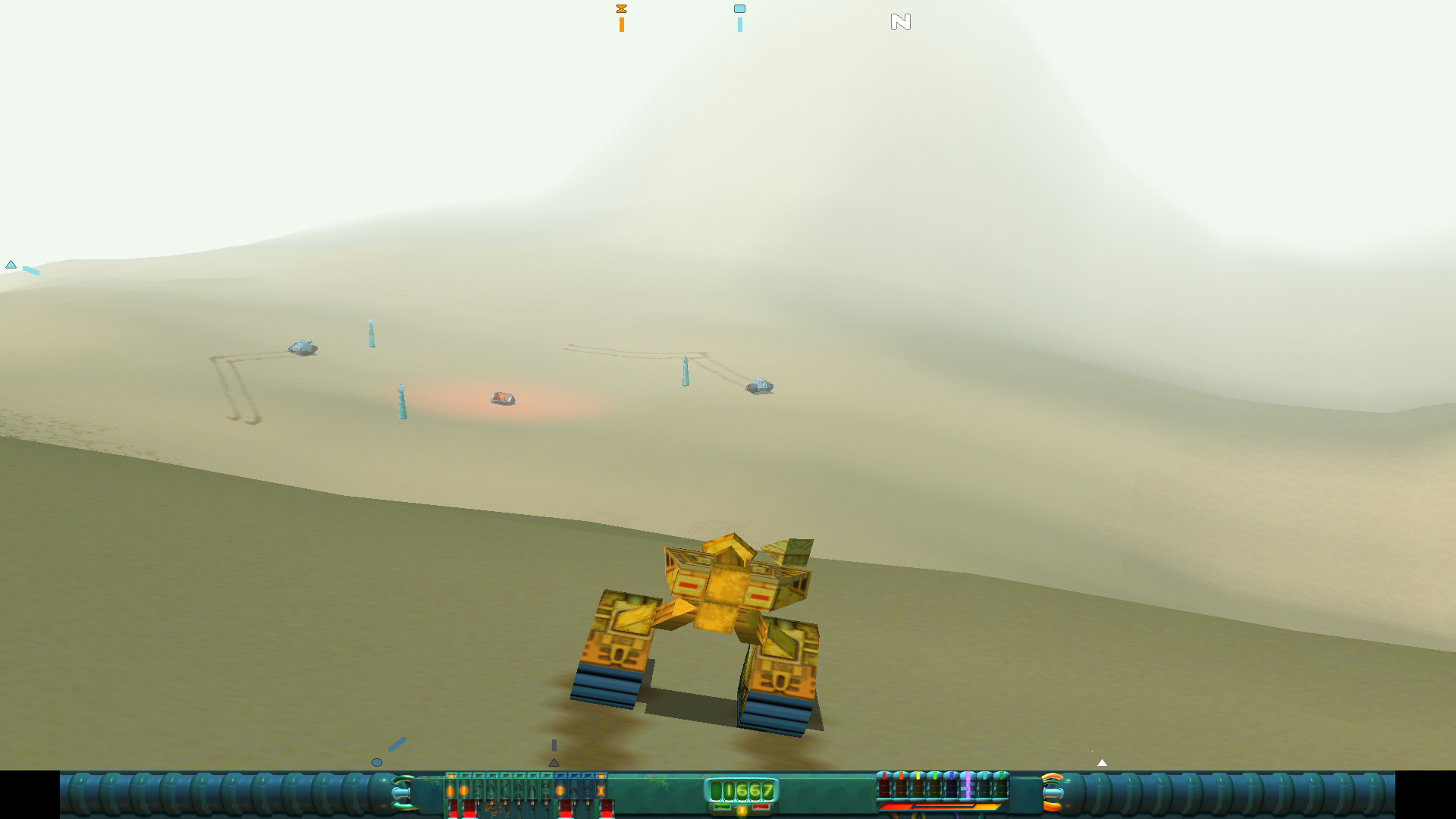

Similar things could be said about Wild Metal Country. In many ways it feels like a glorified tech demo, reminding me of Magic Carpet from 1994, which tried to build an entire game around its deformable terrain but ended up just being a whole bunch of samey levels. Wild Metal Country also has tons of levels, most of which feel the same, and feel like a framework hastily constructed around the core physics of the tanks and their artillery shells. The paper-thin premise is that players are retaking old human colony worlds that were conquered by robots long ago. But the tanks that players use to retake these planets don’t fell very advanced. Most of the time, I was firing off unguided shells, hoping to land them somewhere near the enemy vehicles, while they responded in kind. It’s intentionally clunky, in an endearing way.

Reinforcing this feeling are the strange controls. Wild Metal Country is played entirely with the keyboard, eschewing the usual mouse control of the camera. Number pad keys (of all things) are mapped to the left and right treads of the tank, so each can be operated in forward or reverse, independently of one another. Set both to forward to drive forward. To make a shallow right turn, keep that left tread going but ease up on the right tread. With the left side going faster, the tank will veer to the right. Need to make a sharp left turn? Fire up that right tread, and put the left tread in reverse. That will spin the tank around quickly. Go too fast, however, and you might start skidding around, or even topple over, tumbling end over end down a hill. The physics for this feel great, with different surfaces having different levels of grip, and different tanks handling differently. Just trundling around the polygonal landscapes in a tank is fun, and I could feel the development team’s excitement transferring from the game into my fingertips.

There’s more than just driving around, of course. Tanks can also turn their turrets in a full circle (using the A and D keys), and are therefore able to aim independently of the direction they are driving. The mental gymnastics required to use this effectively reminded me of the torso twist from Mechwarrior 2. Firing a shell is done with the spacebar, but holding the spacebar down will raise the turret to fire in a higher angle arc. Shooting at things therefore becomes a game of judging distance and angle, difficult enough when stationary and downright frantic when moving. Turrets won’t hold their elevated angles either, starting to return to their resting position as soon as the spacebar is released, so repeated shots are difficult. Add to this the fact that explosions from incoming shells can knock the player’s tank around even if they don’t do any direct damage, and exchanges become messy quickly.

The unusual controls and repetitive missions of Wild Metal Country led to a mixed critical response upon release. Playing it now, however, I felt it would go over better today. The gaming landscape has changed a lot since 1999. Back then, there were many fewer games, nearly all of them from major studios, and each was expected to last players a long time. Today, there are far more games than anyone could be expected to play, and therefore space for many different types. A mood piece that only takes 20 minutes to play may be just as interesting as a big budget role-playing game with a massive scale. And Wild Metal Country works surprisingly well as a mood piece. Missions feel larger than they actually are, especially because there’s no map and only a vague radar for guidance. Enemy tanks are uncommon, which means the player’s tank is simply driving around empty landscapes much of the time. There’s no music, just the low growl of the engines. Sometimes flocks of birds fly past overhead. One detail I particularly liked is the way passing clouds cast shadows that move slowly across the terrain. Driving around these places is relaxing, which is certainly not what I expected.

The goal of every mission is the same: find all eight color-coded power cores and return them to one of the extraction points. In practice this usually means searching the area for entrenched enemy positions and assaulting them. This can be done however a player wishes. Charge straight in, or manage to climb up a ridge and drop in from behind. Go in with just the starting shells, or look around for supply drops first. There are several other shell types available, including a bouncy shell, homing missile shell, and a shell designed to explode above a stationary target and rain cluster bombs down on it. There are also mines that can be dropped, although I rarely used these. All this extra weaponry is picked up in crates dropped by the ever-present helicopters, which fly around the map and can be summoned to assist an overturned tank. Why don’t the helicopters just go bomb the targets, instead of leaving the job to an awkward tank? We may never know. The ways of the helicopters are mysterious. Their presence soon becomes just another background detail to these strange worlds.

I knew from the start that Wild Metal Country wouldn’t hold my attention for its entire length, but I found myself returning to it more than I expected. Whereas players in 1999 were probably looking for exciting action, I turned to Wild Metal Country to unwind, to trundle around a barren landscape in a lonely tank, and occasionally exchange a salvo or two with an enemy. I don’t know if the developers were aiming for this feeling of desolation, of empty land with only an occasional sign of life, but it’s what I felt when playing. I also warmed to the combat more than expected. Capturing power cores reminded me of Outcast, in that I was free to plan my own assault however I pleased. I enjoyed the use of elevation in the missions, with some areas only accessible from certain directions due to sheer cliffs on other sides. Sometimes I was navigating narrow ravines with low visibility. Other times I found a high road spanning half the map, with its own set of enemy installations separate from those below.

I did find that, in later missions, the higher enemy presence began to erode the lonely feeling that was so striking at the start. It was cool to see enemy patrols in the distance, but it meant I ran into fights all too quickly. Still, I surprised myself by completing the entire first desert world. I didn’t get far in the tundra world that followed, however, before losing interest. Its ice plains and green underbrush are less evocative than the sand dunes and robotically enhanced pyramids of the desert world. But what really frustrated was the way it changed the rules for when my tank was destroyed. On the desert world, after respawning in a new tank, I could return to where my old tank had exploded and retrieve what it had been carrying, including ammo for the more advanced shells. On the tundra world, any fancy shells are lost when a tank is lost, which meant I was reduced to using the standard, dumb-fire shells pretty much all the time. With both the scenery and the combat less interesting than before, my interest faded and I moved on to other games.

But I’m glad I tried Wild Metal Country. It’s such a weird thing. It’s built with a tiny set of ingredients: futuristic tanks, landscapes, driving physics and impact physics from explosions. Then it adds a custom designed control scheme that ensures combat is slow-paced and imprecise, and level design that manages to evoke a sense of isolation punctuated with occasional spurts of action, all the more impressive given that the areas aren’t actually that big. There are far too many missions for its own good, but this formula works for a surprisingly long time.

If you’re in a curious mood, it’s worth a look, but don’t expect many concessions to your modern PC. When installing Wild Metal Country I was convinced it wouldn’t work, given that the installer was clearly made for an ancient version of Windows and required some legacy drivers. To my surprise, it ran fine once I got that sorted out, and even scaled up to 1920×1080 resolution (although I didn’t realize until writing this that it does so by stretching a 4:3 aspect ratio image, so running letterboxed in 4:3 is probably better). It did show a Windows border around the edges of the screen, but that is easily rectified with a fan fix. Also, note that it appears to be capped at around 30 frames per second, I assume due to its physics modeling. More importantly, the free release from Rockstar Games is no longer available, and as far as I can tell the game is no longer sold anywhere. But enterprising players can likely find the installer archived somewhere.

I haven’t decided yet if I will start regularly picking things at random from my backlog, and make this into a series. I suspect it will be a more sporadic thing. If I do decide to roll the digital dice again, I’ll be sure to write about it here.

Kelvin Green

I do miss this “high concept” method of games design, where they start with a single gameplay gimmick and build the game from there. Games have become more of a storytelling medium these days, so these sorts of games-as-games are rare. I think they were probably more common in the old days, because if you only have 48k (or whatever) of memory to play with, you have to start from a compelling gameplay element.

You still get it in the thriving indie community of course, and there’s an argument that sport games by their very nature count, but the last mainstream game I remember having this sort of “here’s a toy, go and play with it” approach was Katamari Damacy and its sequels.

Lest I come across as a grumpy old grognard, I should point out that I love all sorts of games, and I enjoy modern mainstream releases just as much as the old classics or obscure curios. I also understand why an industry that makes so much money has moved the way it has, so none of this should be seen as a complaint!

Waltorious

Yeah, these kinds of concept-driven games seem to have been more common in the past. I suspect it’s a combination of less entrenched genres and control schemes and the fact that games could be made more quickly by smaller teams. Sure, there are indie games with small teams these days, but they’re often making things based on established templates. Weird ones still come along though. I’ve been meaning to check out Snake Pass, which tasks players with moving like a snake does, using winding slithering maneuvers to traverse the levels and climb obstacles. It sounds pretty cool.