Other History Lessons posts can be found here. If you’re looking specifically for console games, those are here. As always, you may click on images to view larger versions.

For those just tuning in, I’ve been playing early console role-playing games (and some adjacent games) for this sub-series of my broader History Lessons series. I’m nominally trying to go chronologically by the original release date (which is usually the Japanese release date) but I keep expanding the scope to include more games, so I keep jumping back and forth. The farthest I’ve made it in time is SpellCaster for the Sega Master System, which released on September 23, 1988. But I’m currently on a trip back to 1987 to fill in a few games I realized I should have included. The most recent of these is Faxanadu, by Hudson Soft, which released in Japan on November 16, 1987, and was later brought to the US in August 1989.

Faxanadu is a spinoff of Nihon Falcom’s Dragon Slayer series, which I had originally decided to exclude from this series, since they started on Japanese home computer systems rather than consoles, and because the early entries seemed pretty rudimentary. The series was hugely influential in Japan, however, and I eventually decided it was worth including some entries. Specifically, Dragon Slayer IV: Drasle Family, which (unlike the earlier entries) actually came to the US as a port for the Nintendo Entertainment System under the name Legacy of the Wizard. Once that was in, I figured I should probably include Faxanadu too. Although now that I’ve played it, I realize that I should have included it as soon as I decided to tackle action role-playing games along with the more traditional turn-based variety. Of all of the action role-playing hybrids I’ve played so far for this series — as many as seventeen of them, depending on how strictly they’re defined — Faxanadu feels the most like a role-playing game.

Faxanadu is specifically a spinoff of the second Dragon Slayer game, Xanadu, which I have not played. Nihon Falcom licensed it to Hudson Soft to create a game for Nintendo’s Famicom console. That’s where the name comes from, see: it’s the FAmicom spinoff of Xanadu. Of course, players in the US had never heard of Xanadu or any of the rest of the Dragon Slayer games, since those that did get localized had their names changed, so Faxanadu just seemed like an original title with a weird name. I never knew anyone who owned it at the time, but I do remember reading about it in Nintendo Power magazine, which published a guide for the early part of the game, including a map. I remember being awed that the world of Faxanadu was not one of sequential platformer levels, but a single interconnected world, dotted with doorways leading to towers and dungeons. It looked like an epic fantasy adventure, but I never had a chance to try it until now.

The opening of Faxanadu recalls computer role-playing games of that era, like Might and Magic: Book One (the first ever entry in my History Lessons series), in that the player character starts with nothing, and must get outfitted for adventure. Our nameless protagonist returns home to find his elven town under attack, but the townsfolk guide him to see the king, who is looking for any of able body to send for help. Everyone else has already gone, and none have returned. The king gives our hero funds to equip himself, which can then be spent on martial and magical training (allowing the player to use weapons, armor, and magic spells), and on buying (and manually equipping!) meager armor, a small shield, a dagger, and a simple attack spell. Only then can the player fight back against the dwarfs who have gone berserk and are attacking everyone.

All of this preparation promotes a feeling of careful consideration rather than split-second action, and this is borne out in how Faxanadu plays. Critics in the US tended to compare Faxanadu to Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, which I’ve already covered for this series, but it feels very different. Zelda II is an action game first, with smooth, responsive movement that requires quick reaction times to effectively block enemy attacks and land one’s own sword strikes. Its role-playing elements are added on top of this foundation. Faxanadu instead falls back on the role-playing principle that it is the character’s skills and abilities, not the player’s, that matter. The hero’s movement and attacks are slow and deliberate. His shield, which can block incoming magic spells, only partially negates the damage and results in the hero being knocked backwards, so blocking becomes a tactical decision. His jumps are unusual for a platformer, in that he gains height quickly, then hangs in the air near the peak of the jump for longer than expected, before plummeting to the ground all of a sudden at the end. These are not jumps that enable precision maneuvering, they’re clumsy and mostly useful for simple navigation, not for evading attacks.

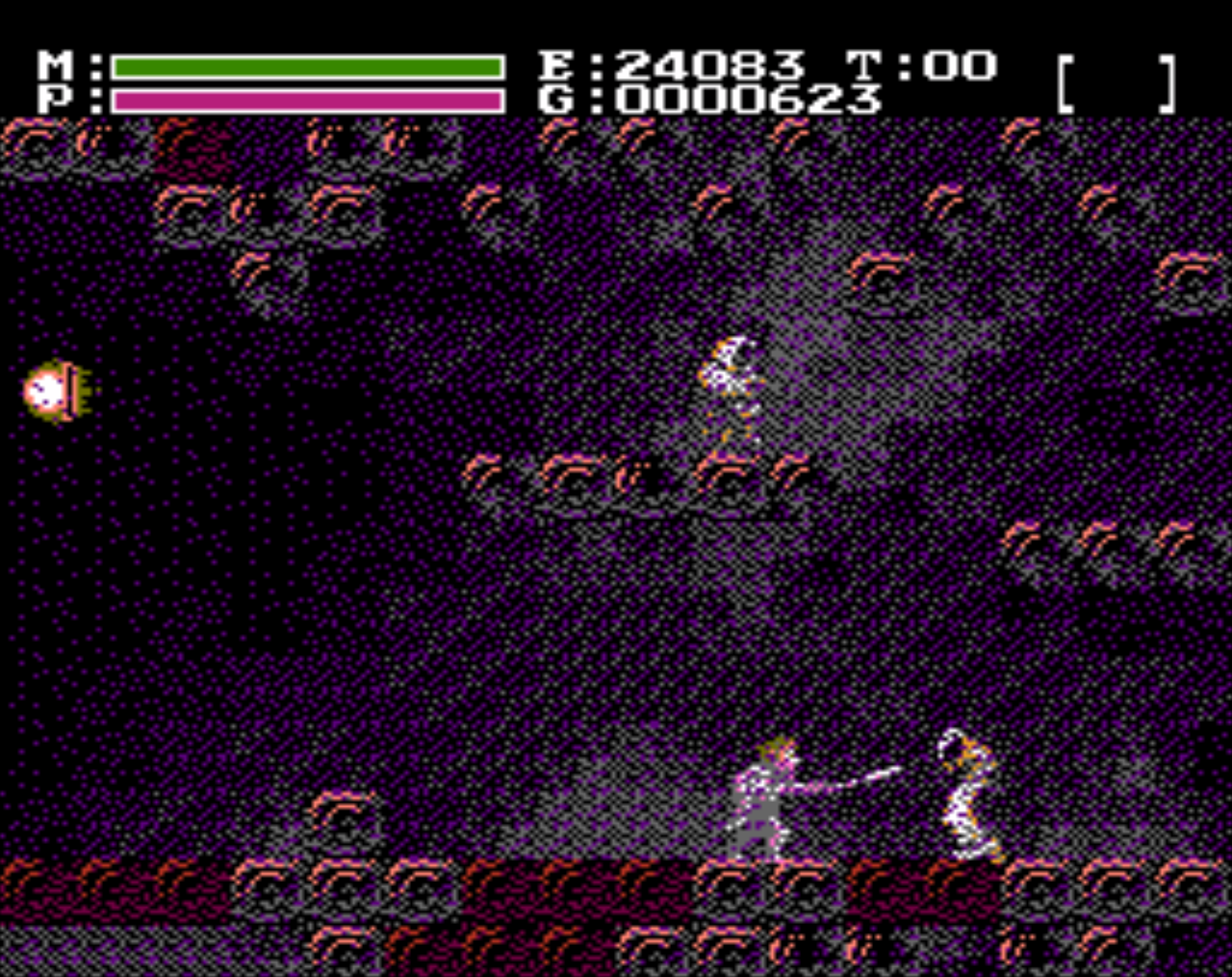

All of this means it’s difficult to emerge from battle unscathed, and the best way to increase survivability is to upgrade the hero’s weapon, armor, shield, and magic. Each of these has several increasingly powerful options that can be purchased from shops, using the gold dropped by defeated enemies. Most shops are in towns, but a few are in harder to reach locations hidden in Faxanadu’s world. The setting is far more interesting than I expected: the hero’s hometown is at the base of the massive World Tree, which he must climb in order to learn what has driven the dwarfs insane and put a stop to it. There are towns within its gargantuan trunk and among the branches of its canopy, and the residents of each provide helpful information about what’s going on. A meteorite has struck the tree, you see, and spread some sort of evil to the dwarfs, who used to be peaceful trade partners with the elven towns. Part of the tree is still burning from the impact, shrouding the area in smoke.

There’s more story in Faxanadu than I expected, and it’s mostly well written. Many games I’ve played for this series have thin premises about rescuing a princess (ugh) or battling some all-powerful evil. Faxanadu is still ultimately about battling a powerful evil, but there’s so much more detail about its world, the elves and the dwarves, and what life used to be like within the World Tree before the meteorite struck. It’s a more mature story, rather than a fairy tale or fable, and it makes me curious to know what the story of the original Xanadu was like. I’ve read that Xanadu is about exploring a subterranean dungeon, so the happenings in the World Tree must be a separate story. But perhaps there are connections or references to Xanadu’s plot?

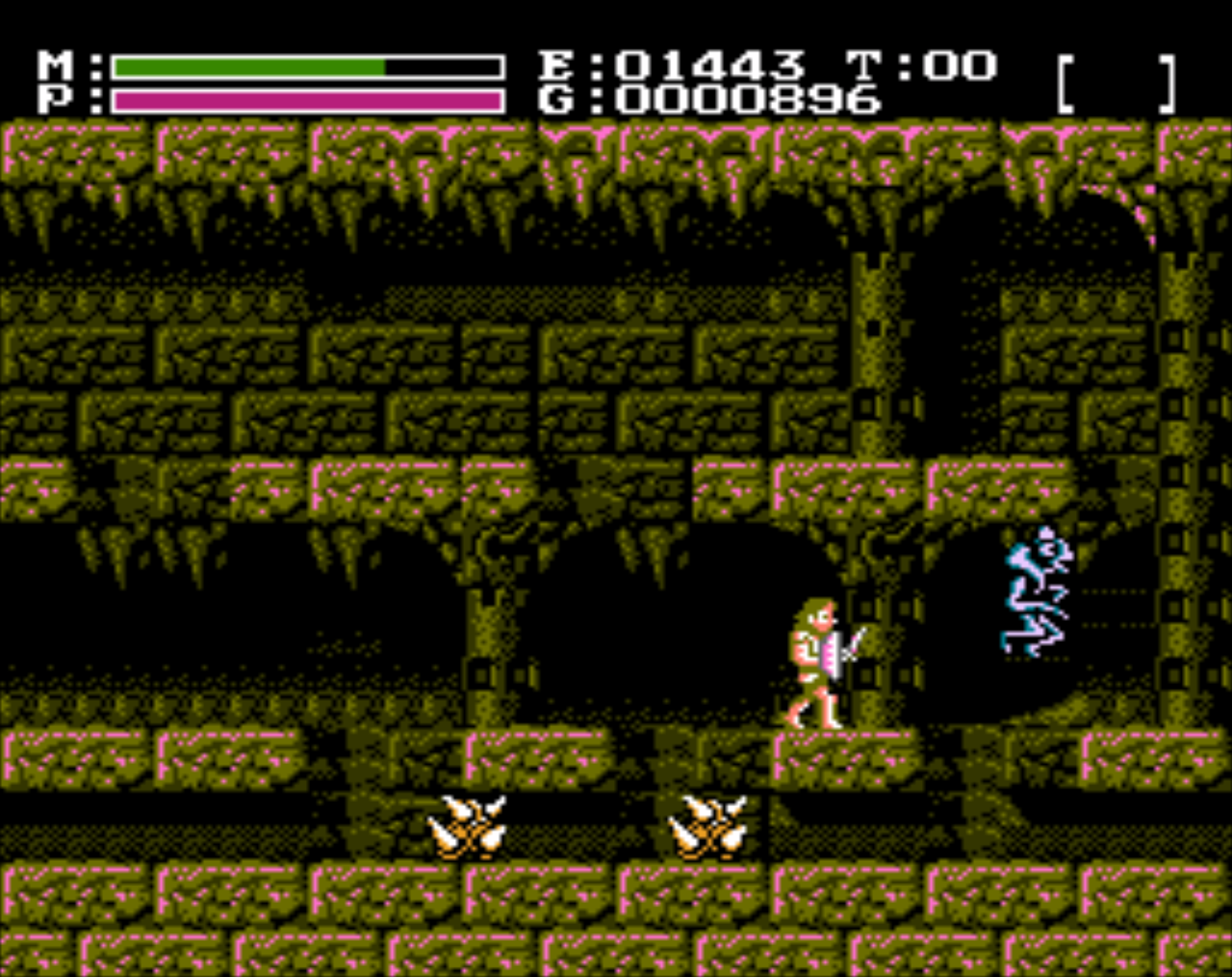

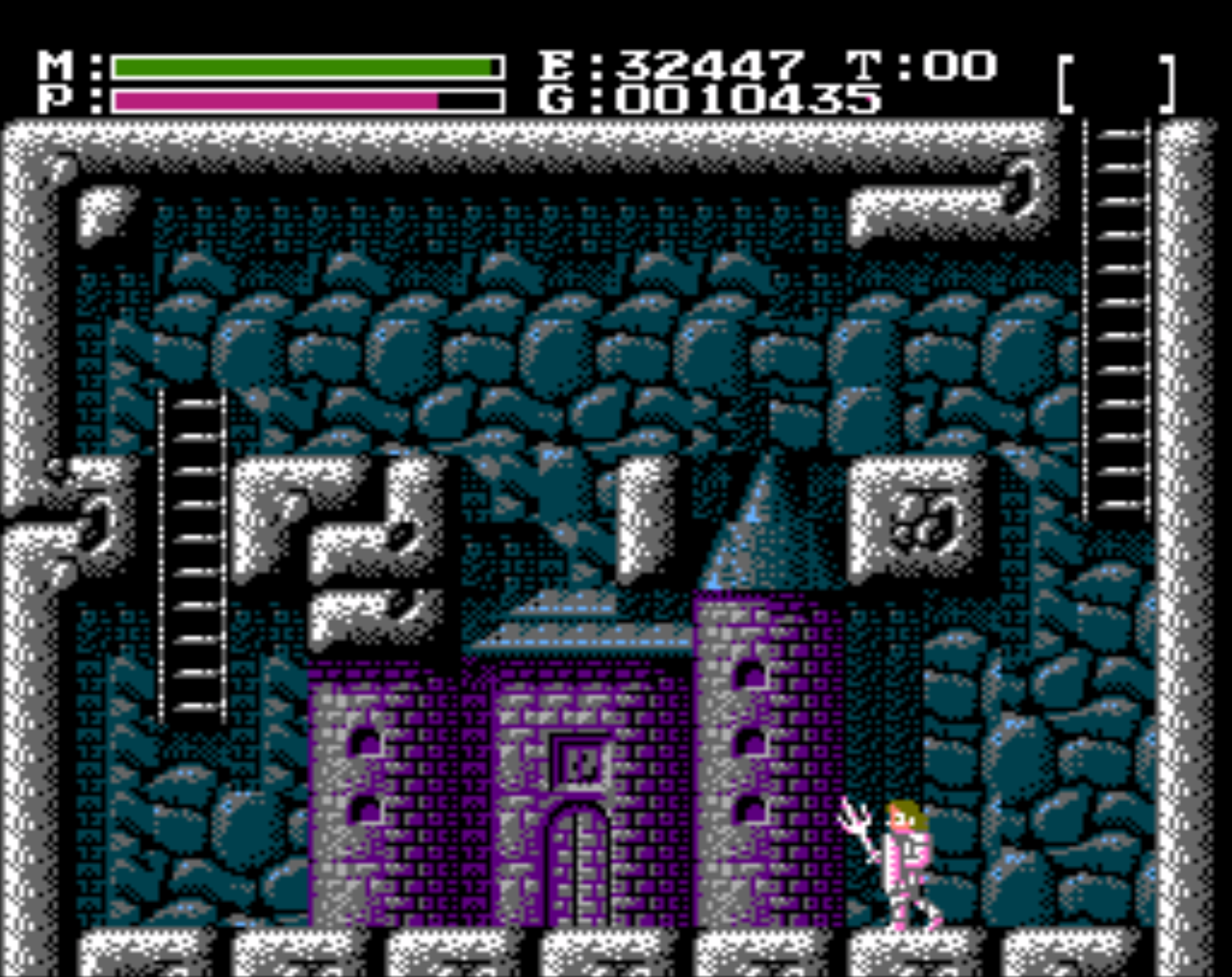

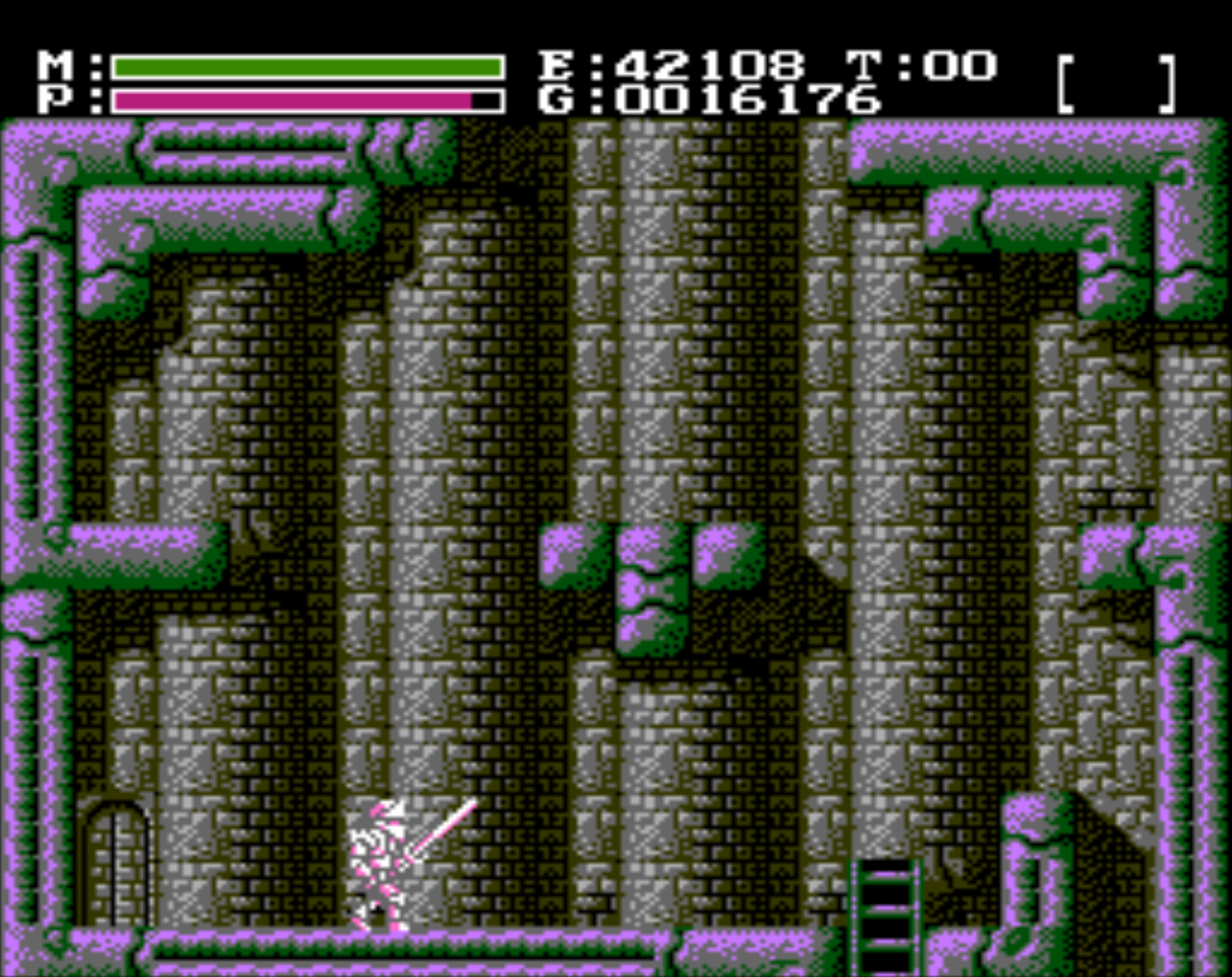

The World Tree and the towns and castles within it have a striking visual style. Unlike most games I’ve played for this series, Faxanadu opts for just one or two dominant colors in each scene, but applies many shades of them to allow for detailed, dramatic backgrounds. Whether it’s the gnarled bark of the World Tree or the dank stone of a gloomy dungeon, every place I explored is wonderfully textured, giving it a real sense of depth. I especially like the buildings that are scattered around. There are a lot of doors leading to other places in Faxanadu, but they are rarely just set into the back wall as in so many other games. No, instead there will be an entire fortified tower built into the tree, complete with stonework with exquisite pixel art capturing the light playing across its cylindrical shape, with a door leading inside. There are buildings like this everywhere, from small shacks to full castles, and they all look really cool.

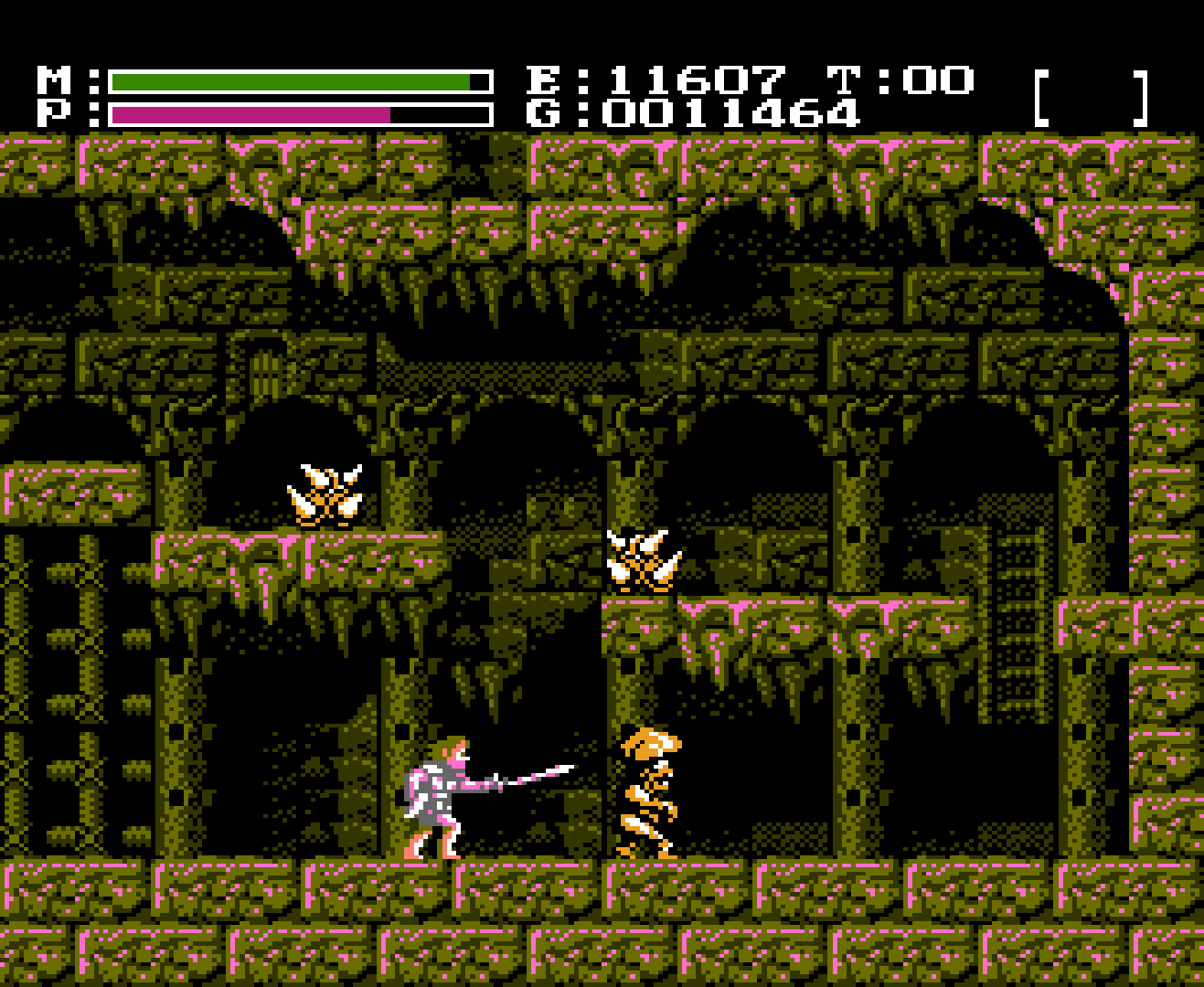

Enemies look cool too, although most don’t look much like dwarfs. I didn’t mind (and it’s partially explained by the evil magic of the meteorite transforming the dwarfs into twisted creatures). One of the first monsters I encountered was a sort of giant head attached to a single, beefy leg, which it used to leap towards me. There are robed wizards whose faces are obscured by their hoods, cunning demonic creatures, some sort of mushroom men, and lamprey-like giant tentacles, to name a few. Both they and the hero are carefully animated, with more animation frames than I expected for every motion, be it a monster’s leap, the hero’s attack, or even just the hero’s walk as he explores the World Tree. I was particularly impressed by the coins dropped from defeated enemies, which spin and bounce when they could have just been static sprites like so many other contemporary games. Every new piece of equipment changes the hero’s appearance too, reinforcing the sense of increasing prowess as he battles enemies that would have felled him easily before.

The enemies are generally quite dangerous, even so. Most have tricky attack patterns, running and jumping around or swooping in wide arcs if they can fly, and most take multiple blows before they fall. Paired with the right platform layouts, the enemies can pose quite the navigational challenge, especially given the hero’s methodical movements I discussed above. I developed tactics for each foe, but usually still sustained a lot of damage. Thankfully, the hero’s health bar is generous, but if he falls in battle, he must restart from the last guru he visited (usually in a church in town).

The gurus are tied to progress in Faxanadu. Not only to they provide passwords in the form of “mantras” that let players continue playing from where they left off (although I used save states rather than go through the tedium of entering passwords), they will also award the hero a new title if he has earned enough experience points from defeating enemies. Interestingly, these do not actually increase the hero’s prowess. Instead, new titles allow him to restart after death (or after returning via a password) with more gold, so he can buy items before heading into the fray once more. This isn’t usually enough to buy new equipment, but it’s enough for some consumable items, which are very helpful. Red potions will fully restore the hero’s health, provided players are quick enough to manually drink them before sustaining a killing blow, and I quickly learned to carry several with me at all times. But just as important are the single-use keys, which come in different types and are needed for opening doors to the various towers, dungeons and castles that the hero must brave in his quest.

This bit of design can be frustrating. I often found myself purchasing several keys just in case, unsure of what locked doors I might encounter. Since they are consumed when used, I might need several copies of the same key in order to proceed, and there’s no way to know ahead of time. It’s possible to sell items back to the shops, but only if the shop stocks that same item. That meant I found myself stuck with a useless early key in my inventory for the second half of the game, because the key shops in the later towns no longer kept those keys in stock. A key is needed every time the hero uses that particular door, too, which is annoying because falling in battle and restarting at the guru means players only keep the items they hadn’t used. Nor do they get to keep the gold they’d collected from enemies. Surviving long enough to make it back to town alive, then, is critical for making progress, since it lets players earn enough cash to buy the new equipment the hero sorely needs. It also helps with accumulating enough experience to advance to the next title, which means more starting gold and less hassle getting back into the adventure.

Still, the unlimited restarts are actually pretty generous compared to some other contemporary games. They help with a sense of continual forward progress, as the hero ascends the huge World Tree and learns more about the threat of the meteorite. But that does mean that the world is more linear than I expected. There are optional places to explore, and an excellent early section with multiple objectives that can be pursued in any order, but on the whole there’s a lot less backtracking than in games like Metroid or Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest. There was one place where I found a shop selling powerful equipment for prices far higher than I could afford, so I moved on… but later realized I could actually make my way back there, because the item needed to access it was not unique after all: I’d found a shop selling it in a later town. I traveled back and was able to buy some stuff that leapfrogged a tier in quality (they were, of course, available to buy again later in the game). But that was the only time that I wasn’t moving forward.

It wasn’t the only time that I got to reuse items I thought were one-time things, though. There’s a point in the game where the hero must use winged boots, which allow him to fly for a short time, to progress. After that it didn’t seem like winged boots were going to be of much use, and they’re expensive, so I didn’t bother buying another pair. But later I found some winged boots during my explorations, and I was able to use them to get around more easily, potentially skipping entire difficult paths I would have had to take otherwise. Where another game would have limited the boots to the specific place they’re needed, Faxanadu let me use them whenever I wanted, committing to an internal logic of its world over a carefully scripted experience for the player. Yet another way in which it recalls its role-playing peers more than its action cousins.

Faxanadu also captures the typical role-playing game satisfaction of building up a character until they are a powerful hero. By the time I reached the final areas of the game, I’d collected the most powerful equipment and magic, and I faced the twisted passages full of dangerous foes with confidence. I realized that I’d missed this type of payoff for taking a character from mere mortal to legendary champion. The more action-focused games I’ve played recently for this series haven’t had the same feeling of progression, and finding it in Faxanadu reminded me how satisfying it is. It pairs so well with the typical role-playing story about facing a formidable evil, by emphasizing the struggle required to overcome such an adversary.

Overall, I was very impressed with Faxanadu, and surprised it isn’t better known. It’s not exactly obscure, but it’s not often mentioned among the classic games for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). It deserves to be, though. It’s a solidly designed and engaging adventure, and I’m glad I went back to play it. If you want to check it out yourself, emulation is likely the only option, as the only re-release it ever got was for the now-discontinued Wii Virtual Console. I played via emulation via the Retroarch frontend and Mesen core, as I have done for other NES games in this series.

This doesn’t quite bring us back into chronological order, though. Up next is yet another entry in the Dragon Slayer series that I originally skipped. Stay tuned!

Next on Console History: Sorcerian

thekelvingreen

Huh, I had no idea about the title. That’s quite fun, and I’m glad they didn’t change it for the western release.

I’m not a huge fan of NES graphics, probably as they always seem a bit washed out and dull in comparison to the Master System and even he home computers I grew up with, but I am impressed with what has been achieved with this game. It looks great, and the detail makes it seem almost 16-bit. It’s very nice.

Waltorious

Yeah, this one really made me stop and admire the pixel art, more so than for most games in this series so far. I do agree that the Master System games I’ve covered seem more vibrant than their NES counterparts in general. The Master System did have ten more colors (including seven more displayable simultaneously) after all.

Which home computer systems did you grow up with? I feel like I missed that era of computing. I had an NES as a kid, but the first home computer system I remember my family getting was an IBM-compatible that ran DOS. And while Wikipedia tells me that VGA was introduced in 1987, I don’t remember playing games in VGA until later; the DOS games I was playing around the time I got my NES looked (and sounded!) significantly worse. That didn’t stop me from getting into PC games, of course.

thekelvingreen

I grew up with a whole bunch of computers; the BBC Model B, the C64, Amstrad 464, Spectrum 48k, Acorn Electron, and various Amigas. Here in the UK we had our own weird little computer scene so even with machines that were also available in the US, like the Commodore family, our games were very different.

gamer indreams

I never got to play this but I had the VG&CE magazine that had the guide for it and I’ve read it so many times that I feel like I played it

https://archive.org/details/vgce_90-06/page/74/mode/2up

Seeing you appreciate the game makes me feel like I really need to go back and spend a little time trying to play it!